The Montford Delusion

If you don’t know much about climate science, or about the details of the controversy over the “hockey stick,” then A. W. Montford’s book The Hockey Stick Illusion: Climategate and the Corruption of Science might persuade you that not only the hockey stick, but all of modern climate science, is a fraud perpetrated by a massive conspiracy of climate scientists and politicians, in order to guarantee an unending supply of research funding and political power. That idea gets planted early, in the 6th paragraph of chapter 1.

The chief focus is the original hockey stick, a reconstruction of past temperature for the northern hemisphere covering the last 600 years by Mike Mann, Ray Bradley, and Malcolm Hughes [Nature, 392 (1998) 779, doi: 10.1038/33859, available here], hereafter called “MBH98″ (the reconstruction was later extended back to a thousand years by Mann et al., 1999, or “MBH99″ ). The reconstruction was based on proxy data, most of which are not direct temperature measurements but may be indicative of temperature. To piece together past temperature, MBH98 estimated the relationships between the proxies and observed temperatures in the 20th century, checked the validity of the relationships using observed temperatures in the latter half of the 19th century, then used the relationships to estimate temperatures as far back as 1400. The reconstruction all the way back to the year 1400 used 22 proxy data series, although some of the 22 were combinations of larger numbers of proxy series by a method known as “principal components analysis” (hereafter called “PCA,” see here). For later centuries, even more proxy series were used. The result was that temperatures had risen rapidly in the 20th century compared to the preceding 5 centuries. The sharp “blade” of 20th-century rise compared to the flat “handle” of the 15th-19th centuries was reminiscent of a “hockey stick” — giving rise to the name describing temperature history.

But if you do know something about climate science and the politically motivated controversy around it, you might be able to see that reality is the opposite of the way Montford paints it. In fact, Montford goes so far over the top that if you’re a knowledgeable and thoughtful reader, it eventually dawns on you that the real goal of those whose story Montford tells is not to understand past climate, it’s to destroy the hockey stick by any means necessary.

Montford’s hero is Steve McIntyre, portrayed as a tireless, selfless, unimpeachable seeker of truth whose only character flaw is that he’s just too polite. McIntyre, so the story goes, is looking for answers from only the purest motives but uncovers a web of deceit designed to affirm foregone conclusions whether they’re so or not — that humankind is creating dangerous climate change, the likes of which hasn’t been seen for at least a thousand or two years. McIntyre and his collaborator Ross McKitrick made it their mission to get rid of anything resembling a hockey stick in the MBH98 (and any other) reconstruction of past temperature.

Principal Components

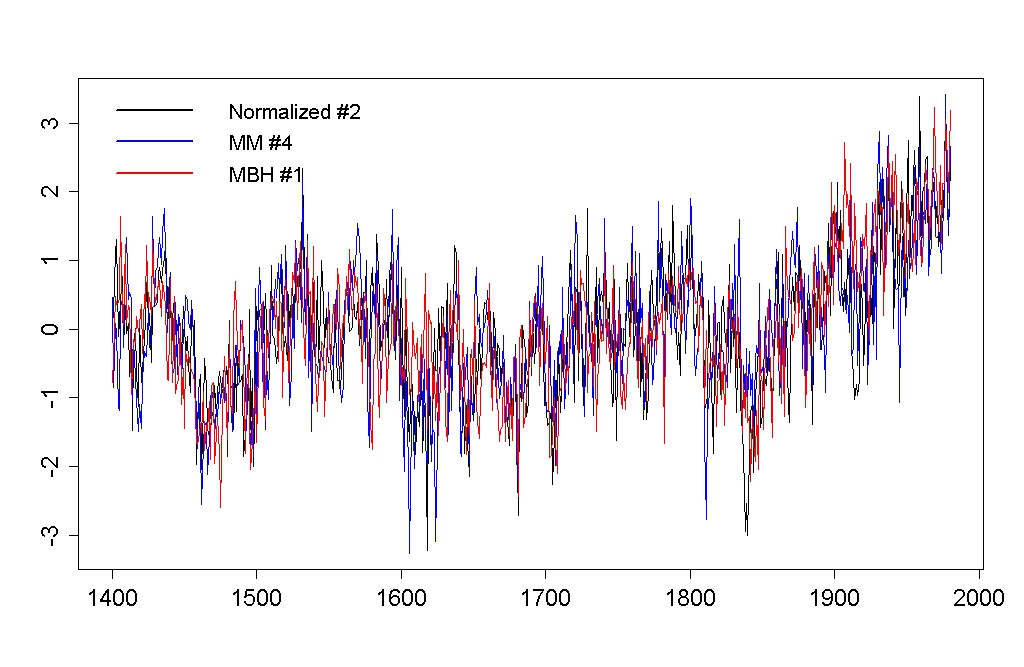

For instance: one of the proxy series used as far back as the year 1400 was NOAMERPC1, the 1st “principal component” (PC1) used to represent patterns in a series of 70 tree-ring data sets from North America; this proxy series strongly resembles a hockey stick. McIntyre and McKitrick (hereafter called “MM”) claimed that the PCA used by MBH98 wasn’t valid because they had used a different “centering” convention than is customary. It’s customary to subtract the average value from each data series as the first step of computing PCA, but MBH98 had subtracted the average value during the 20th century. When MM applied PCA to the North American tree-ring series but centered the data in the usual way, then retained 2 PC series just as MBH98 had, lo and behold — the hockey-stick-shaped PC wasn’t among them! One hockey stick gone.Or so they claimed. In fact, the hockey-stick shaped PC was still there, but it was no longer the strongest PC (PC1), it was now only 4th strongest (PC4). This raises the question, how many PCs should be included from such an analysis? MBH98 had originally included two PC series from this analysis because that’s the number indicated by a standard “selection rule” for PC analysis (read about it here).

MM used the standard centering convention but applied no selection rule — they just imitated MBH98 by including 2 PC series, and since the hockey stick wasn’t one of those 2, that was good enough for them. But applying the standard selection rules to the PCA analysis of MM indicates that you should include five PC series, and the hockey-stick shaped PC is among them (at #4). Whether you use the MBH98 non-standard centering, or standard centering, the hockey-stick shaped PC must still be included in the analysis.

It was also pointed out (by Peter Huybers) that MM hadn’t applied “standard” PCA either. They used a standard centering but hadn’t normalized the data series. The 2 PC series that were #1 and #2 in the analysis of MBH98 became #2 and #1 with normalized PCA, and both should unquestionably be included by standard selection rules. Again, whether you use MBH non-standard centering, MM standard centering without normalization, or fully “standard” centering and normalization, the hockey-stick shaped PC must still be included in the analysis.

In reply, MM complained that the MBH98 PC1 (the hockey-stick shaped one) wasn’t PC1 in the completely standard analysis, that normalization wasn’t required for the analysis, and that “Preisendorfer’s rule N” (the selection rule used by MBH98) wasn’t the “industry standard” MBH claimed it to be. Montford even goes so far as to rattle off a list of potential selection rules referred to in the scientific literature to give the impression that the MBH98 choice isn’t “automatic,” but the salient point which emerges from such a list is that MM never used any selection rules — at least, none that are published in the literature.

The truth is that whichever version of PCA you use, the hockey-stick shaped PC is one of the statistically significant patterns. There’s a reason for that: the hockey-stick shaped pattern is in the data, and it’s not just noise, it’s signal. Montford’s book makes it obvious that MM actually do have a selection rule of their own devising: if it looks like a hockey stick, get rid of it.

The PCA dispute is a prime example of a recurring McIntyre/Montford theme: that the hockey stick depends critically on some element or factor, and when that’s taken away the whole structure collapses. The implication that the hockey stick depends on the centering convention used in the MBH98 PCA analysis makes a very persuasive “Aha — gotcha!” argument. Too bad it’s just not true.

Different, yes. Completely, no.

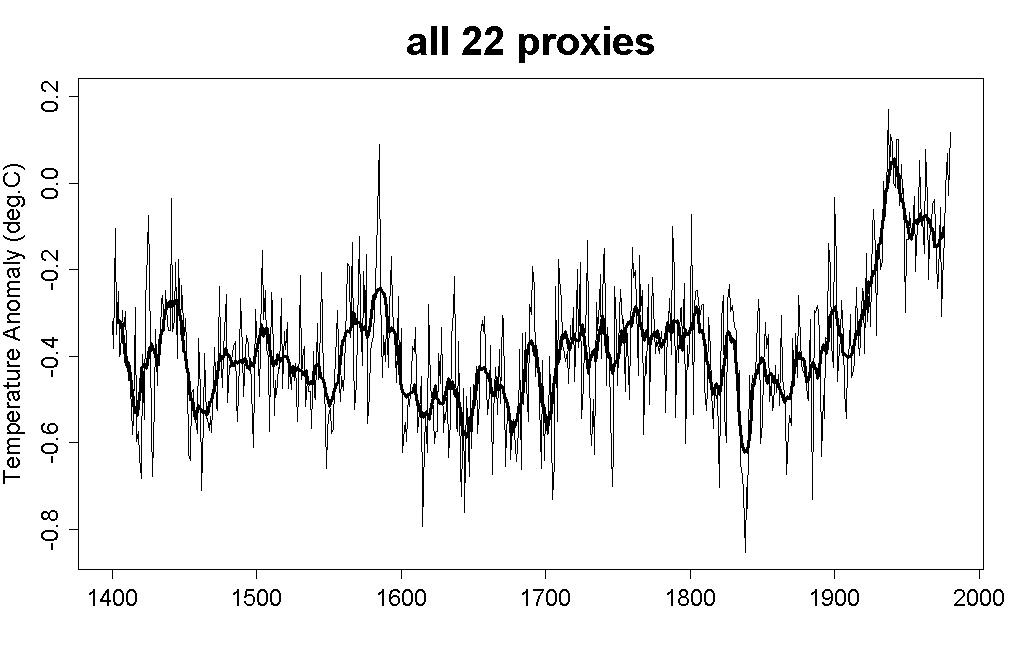

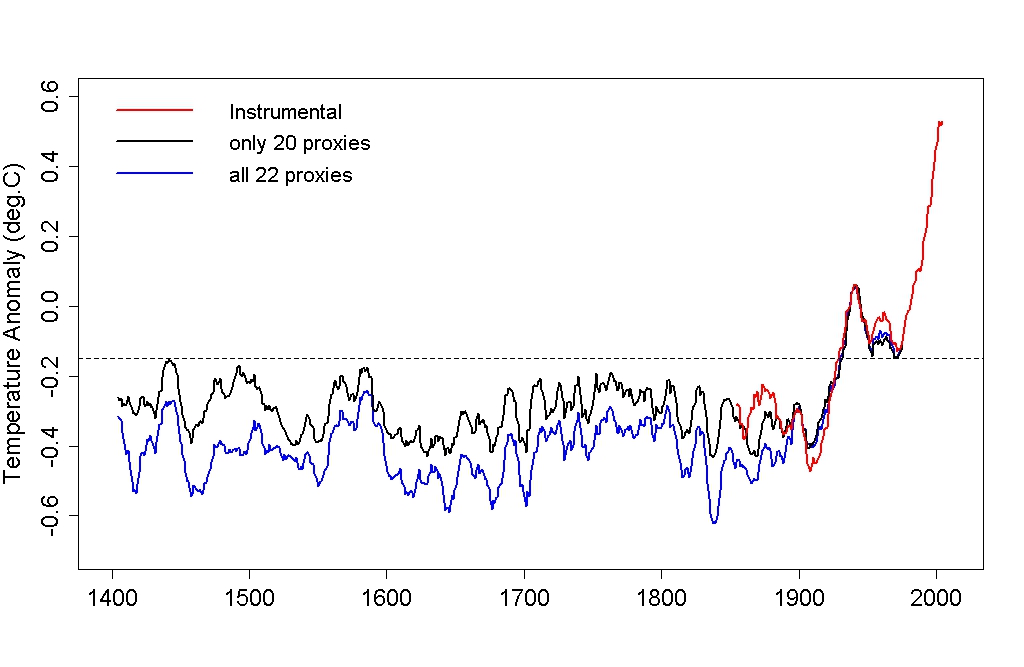

As another example, Montford makes the claim that if you eliminate just two of the proxies used for the MBH98 reconstruction since 1400, the Stahle and NOAMER PC1 series, “you got a completely different result — the Medieval Warm Period magically reappeared and suddenly the modern warming didn’t look quite so frightening.” That argument is sure to sell to those who haven’t done so. But I have. I computed my own reconstructions by multiple regression, first using all 22 proxy series in the original MBH98 analysis, then excluding the Stahle and NOAMER PC1 series. Here’s the result with all 22 proxies (the thick line is a 10-year moving average):

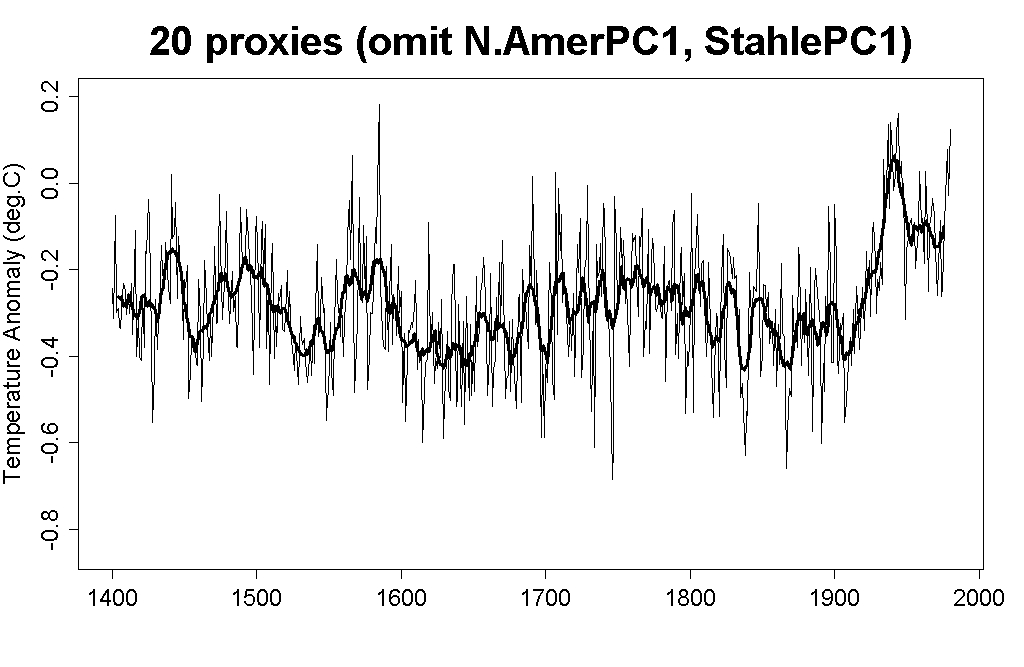

Here it is with just 20 proxies:

Finally, here are the 10-year moving average for both cases, and for the instrumental record:

Certainly the result is different — how could it not be, using different data? — but calling it “completely different” is just plain wrong. Yes, the pre-20th century is warmer, with the 15th century a wee bit warmer still — but again, how could it not be when eliminating two hand-picked proxy series for the sole purpose of denying the unprecedented nature of modern warming? Yet even allowing this cherry-picking of proxies is still not enough to accomplish McIntyre’s purpose; preceding centuries still don’t come close to the late-20th century warming. In spite of Montford’s claims, it’s still a hockey stick.

Beyond Reason

Another of McIntyre’s targets was the Gaspe series, referred to in the MBH98 data as “treeline-11.” It just might be the most hockey-stick shaped proxy of all. This particular series doesn’t extend all the way back to the year 1400 — it doesn’t start until 1404 — so MBH98 had extended the series back four years by persistence — taking the earliest value and repeating it for the preceding four years. This is not at all an unusual practice, and — let’s face facts folks — extending 4 years out of a nearly 600-year record on one out of 22 proxies isn’t going to change things much. But McIntyre objected that the entire Gaspe series had to be eliminated because it didn’t extend all the way back to 1400. This argument is downright ludicrous — what it really tells us is that McIntyre and McKitrick are less interested in reconstructing past temperature than in killing anything that looks like a hockey stick.McIntyre also objected that other series had been filled in by persistence, not on the early end but on the late end, to bring them up to the year 1980 (the last year of the MBH98 reconstruction). Again, this is not a reasonable argument. Mann responded by simply computing the reconstruction you get if you start at 1404 and end at 1972, so you don’t have to do any infilling at all. The result: a hockey stick.

Again, we have another example of Montford implying that some single element is both faulty and crucial. Without nonstandard PCA the hockey stick falls apart! Without the Stahle and NOAMER PC1 data series the hockey stick falls apart! Without the Gaspe series the hockey stick falls apart! Without bristlecone pine tree rings the hockey stick falls apart! It’s all very persuasive, especially to the conspiracy-minded, but the truth is that the hockey stick depends on none of these elements. You get a hockey stick with standard PCA; in fact, you get a hockey stick using no PCA at all. Remove the NOAMER PC1 and Stahle series, you’re left with a hockey stick. Remove the Gaspe series, it’s still a hockey stick.

As a great deal of other research has shown, you can even reconstruct past temperature without bristlecone pine tree rings, or without any tree ring data at all, resulting in: a hockey stick. It also shows, consistently, that nobody is trying to “get rid of the medieval warm period” or “flatten out the little ice age” since those are features of all reconstructions of the last 1000 to 2000 years. What paleoclimate researchers are trying to do is make objective estimates of how warm and how cold those past centuries were. The consistent answer is, not as warm as the last century and not nearly as warm as right now.

The hockey stick is so thoroughly imprinted on the actual data that what’s truly impressive is how many things you have to get rid of to eliminate it. There’s a scientific term for results which are so strong and so resistant to changes in data and methods: robust.

Cynical Indeed

Montford doesn’t just criticize hockey-stick shaped proxies, he bends over backwards to level every criticism conceivable. For instance, one of the proxy series was estimated summer temperature in central England, taken from an earlier study by Bradley and Jones (1993, the Holocene, 3, 367-376). It’s true that a better choice for central England would have been the central England temperature time series (CETR), which is an instrumental record covering the full year rather than just summertime. The CETR also shows a stronger hockey-stick shape than the central England series used by MBH98, in part because it includes earlier data (from the late 17th century) than the Bradley and Jones dataset. Yet Montford sees fit to criticize their choice, saying “Cynical observers might, however, have noticed that the late seventeenth century numbers for CETR were distinctly cold, so the effect of this truncation may well have been to flatten out the little ice age.”In effect, even when MBH98 used data which weakens the difference between modern warmth and preceding centuries, they’re criticized for it. Cynical indeed.

Face-Palm

The willingness of Montford and McIntyre to level any criticism which might discredit the hockey stick just might reach its zenith in a criticism which Montford repeats, but is so nonsensical that one can hardly resist the proverbial “face-palm.” Montford more than once complains that hockey-stick shaped proxies dominate climate reconstructions — unfairly, he implies — because they correlate well to temperature.Duh.

Guilty

Criticism of MBH98 isn’t restricted to claims of incorrect data and analysis, Montford and McIntyre also see deliberate deception everywhere they look. This is almost comically illustrated by Montford’s comments about an email from Malcolm Hughes to Mike Mann (emphasis added by Montford):Mike — the only one of the new S.American chronologies I just sent you that already appears in the ITRDB sets you already have is [ARGE030]. You should remove this from the two ITRDB data sets, as the new version should be different (and better for our purposes).Here’s what Montford has to say:

Cheers,

Malcolm

It was possible that there was an innocent explanation for the use of the expression “better for our purposes,” but McIntyre can hardly be blamed for wondering exactly what “purposes” the Hockey Stick authors were pursuing. A cynic might be concerned that the phrase actually had something to do with “getting rid of the Medieval Warm Period.” And if Hughes meant “more reliable,” why hadn’t he just said so?This is nothing more than quote-mining, in order to interpret an entirely innocent turn of phrase in the most nefarious way possible. It says a great deal more about the motives and honesty of Montford and McIntyre than about Mann, Bradley, and Hughes. The idea that MM’s so-called “correction” of MBH98 “restored the MWP” constitutes a particularly popular meme in contrarian circles, despite the fact that it is quite self-evidently nonsense: MBH98 only went back to AD 1400, while the MWP, by nearly all definitions found in the professional literature, ended at least a century earlier! Such internal contradictions in logic appear to be no impediment, however, to Montford and his ilk.

Conspiracies Everywhere

Montford also goes to great lengths to accuse a host of researchers, bloggers, and others of attempting to suppress the truth and issue personal attacks on McIntyre. The “enemies list” includes RealClimate itself, claimed to be a politically motivated mouthpiece for “Environmental Media Services,” described as a “pivotal organization in the green movement” run by David Fenton, called “one of the most influential PR people of the 20th century.” Also implicated are William Connelly for criticizing McIntyre on sci.environment and James Annan for criticizing McIntyre and McKitrick. In a telling episode of conspiracy theorizing, we are told that their “ideas had been picked up and propagated across the left-wing blogosphere.” Further conspirators, we are informed, include Brad DeLong and Tim Lambert. And of course one mustn’t omit the principal voice of RealClimate, Gavin Schmidt.Perhaps I should feel personally honored to be included on Montford’s list of co-conspirators, because yours truly is also mentioned. According to Montford’s typical sloppy research I have styled myself as “Mann’s Bulldog.” I’ve never done so, although I find such an appellation flattering; I just hope Jim Hansen doesn’t feel slighted by the mistaken reference.

The conspiracy doesn’t end with the hockey team, climate researchers, and bloggers. It includes the editorial staff of any journal which didn’t bend over to accommodate McIntyre, including Nature and GRL which are accused of interfering with, delaying, and obstructing McIntyre’s publications.

Spy Story

The book concludes with speculation about the underhanded meaning of the emails stolen from the Climate Research Unit (CRU) in the U.K. It’s really just the same quote-mining and misinterpretation we’ve heard from many quarters of the so-called “skeptics.” Although the book came out very shortly after the CRU hack, with hardly sufficient time to investigate the truth, the temptation to use the emails for propaganda purposes was irresistible. Montford indulges in every damning speculation he can get his hands on.Since that time, investigations have been conducted, both into the conduct of the researchers at CRU (especially Phil Jones) and Mike Mann (the leader of the “hockey team”). Certainly some unkind words were said in private emails, but the result of both investigations is clear: climate researchers have been cleared of any wrongdoing in their research and scientific conduct. Thank goodness some of those who bought in to the false accusations, like Andy Revkin and George Monbiot, have seen fit actually to apologize for doing so. Perhaps they realize that one can’t get at the truth simply by reading people’s private emails.

Montford certainly spins a tale of suspense, conflict, and lively action, intertwining conspiracy and covert skullduggery, politics and big money, into a narrative worthy of the best spy thrillers. I’m not qualified to compare Montford’s writing skill to that of such a widely-read author as, say, Michael Crichton, but I do know they share this in common: they’re both skilled fiction writers.

The only corruption of science in the “hockey stick” in the minds of McIntyre and Montford. They were looking for corruption, and they found it. Someone looking for actual science would have found it as well.

Link: http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2010/07/the-montford-delusion/#more-4431

No comments:

Post a Comment