September 2, 2019, 1:34 PM EDT

| Above: @astro_christina captured this image of #HurricaneDorian on September 2, 2019 from the space station. |

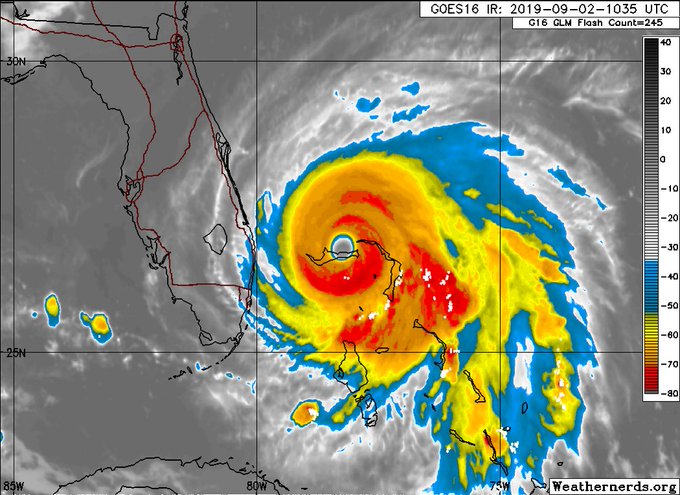

After thrashing Great Abaco Island on Saturday, Dorian has parked over Grand Bahama Island, which has been getting the most fierce and prolonged battering from an extreme Atlantic hurricane in history. According to the NOAA historical hurricane database, the only comparable Category 5 beating is the one administered to Honduras by Hurricane Mitch of 1998, which spent 12 hours within 50 miles of the island of Guanaja as a Category 5 storm. However, Mitch's eye did not stay parked over land like Dorian's has.

At 3 pm EDT, Dorian was centered about 25 miles east-northeast of Freeport, moving west-northwest at just 1 mph. The hurricane’s eyewall has been slamming the island since 9 pm EDT Sunday, and storm surge has been extreme and prolonged over many areas. Sustained winds were 150 mph, not far below Category 5 strength. However, Hurricane Hunters confirmed a break in the eyewall on Monday afternoon, and the central pressure had risen to 941 millibars, so we can expect Dorian's strength to be further downgraded on Monday evening.

“These hazards will continue over Grand Bahama Island during most of the day, causing extreme destruction on the island,” said the National Hurricane Center in a noon update. There have been multiple reports of storm-surge flooding forcing residents to take shelter in attics.

“The Bahamas is presently at war and being attacked by Hurricane Dorian,” Prime Minister Dr. Hubert Minnis told the Nassau Guardian. “And yet, it has no weapon at its disposal to defend itself during such an assault by this enemy.”

This is a topographic map of Grand Bahama island.

Green: 0-15 ft

Yellow: 15-30 ft

Red: 30+ ft

Dorian's storm surge is estimated at 18-23 ft, which would submerge everything in green and significant parts of the yellow. Hopefully most people managed to move to safe locations.

629 people are talking about this

Storm surge: the biggest U.S. threat from Dorian

After days of uncertainty on crucial aspects of Dorian’s track, computer models came into sharper agreement on Sunday night. The 0Z ensemble model runs from the European and GFS models closely agreed that Dorian will arc northeastward just off the coast from east central Florida on Tuesday to south of North Carolina by Friday. A small minority (about 10%) of ensemble tracks produce brief, grazing landfalls.

The latest 12Z Monday runs of the four track models that performed best in the two-day time range in 2018—the European, UKMET, HWRF, and GFS—have all fallen in line with a track about 50 - 80 miles from the coast of Florida and Georgia, then growing very close to the coast or making landfall in the Carolinas. Hurricane watches are not issued until 48 hours before a landfall threat, so we can expect such watches to be extended up the Southeast coast over the next day or two as the threat unfolds. Remember that the average error in a 24-hour NHC forecast is about 40 miles, and a 48-hour forecast is typically in error by about 65 miles.

The long awaited stall of #Hurricane #Dorain occurred last night, unfortunately over #GrandBahama island

As it remains stalled, it is upwelling cooler water underneath. We see this effect via warming cloud tops near the center. More weakening expected in the short term.

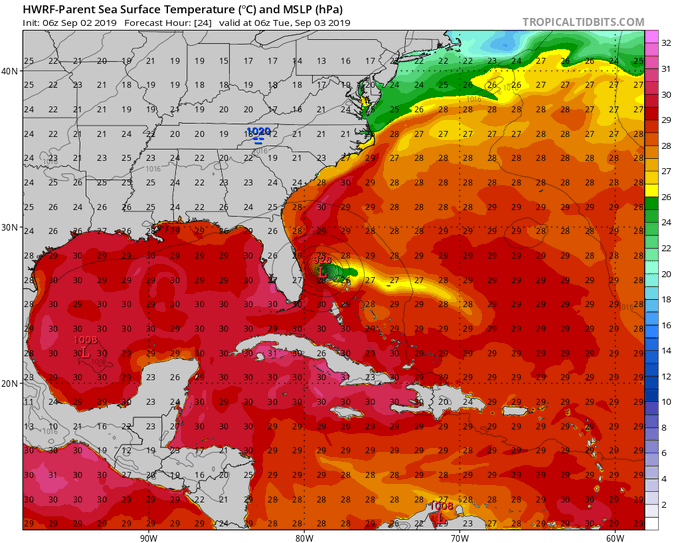

Here is the 24h HWRF forecast for #Dorian parent domain just looking at the SST field underneath. You can follow the cold wake of the storm track, but notice the <26c br="" dorian.="" ssts="" under="">

This would likely induce continued weakening until Dorian moves away from its own cold wake.

32 people are talking about this

Comparing Dorian and Matthew

The consensus track for Dorian bears a close resemblance to that of 2016’s Hurricane Matthew, which caused more than $10 billion in U.S. damage as it curled very near the coast from Florida to North Carolina on a coast-hugging track. The lastest NHC forecast has Dorian following Matthew's track within about 20 miles, all the way from central Florida to South Carolina. What are the similarities and differences?

—Size: Dorian is about the same size as Matthew. During its track up the Southeast U.S. coast, Matthew had hurricane-force winds that extended out about 45 mlies to the northwest of the center, and tropical storm-force winds that extended out about 120 miles. For Wednesday, NHC is predicting that Dorian's hurricane-force and tropical storm-force winds will extend out 40 and 120 miles to the northwest, respectively.

—Speed: Dorian will be a slower mover than Matthew, especially near Florida. Matthew took a day and a half to get from just east of Florida's Space Coast to just south of Wilmington, North Carolina. Dorian is predicted to take about two days to cover the same territory. As a result, water will pile up along the Southeast coast ahead of Dorian for a longer period than with Matthew, and peak flooding may extend over multiple tidal cycles.

—Strength: Dorian will probably be about as strong as Matthew, perhaps a little stronger. Dorian will likely weaken to Category 3 strength as it moves near northern Florida, and it will likely be a Category 1 or 2 off North Carolina. This is quite similar to the weakening that Matthew experienced, although Matthew was already a minimal Category 1 by the time it reached northern South Carolina.

—Track: It’s uncertain at this point exactly where Dorian may track closer to or farther from the coast than Matthew. Matthew made landfall just north of Charleston, South Carolina as a Category 1 hurricane. Dorian is more likely to make landfall in North Carolina, according to the latest NHC forecast.

All told, Dorian will have the potential to produce some of the largest storm surges on record along the Southeast coast, and will likely be a multi-billion dollar storm due to storm surge damages alone. Whether or not local all-time records occur, as they did during Matthew in 2016 at several locations, will hinge on Dorian’s exact track, timing, and strength.

Dorian is not moving into a strong preexisting frontal zone, so rainfall well inland will not be excessive, at least initially. The most concerning area for potential inland flooding is North Carolina, as by the time Dorian reaches this location (around Friday) it may be producing an expansive shield of rains to its north and northeast. Widespread rains of 5-10” and localized amounts well over 10” may be possible across eastern North Carolina, which was devastated by massive inland flooding during Matthew as well as during Florence (2018) and Floyd (1999).

Dorian is not moving into a strong preexisting frontal zone, so rainfall well inland will not be excessive, at least initially. The most concerning area for potential inland flooding is North Carolina, as by the time Dorian reaches this location (around Friday) it may be producing an expansive shield of rains to its north and northeast. Widespread rains of 5-10” and localized amounts well over 10” may be possible across eastern North Carolina, which was devastated by massive inland flooding during Matthew as well as during Florence (2018) and Floyd (1999).

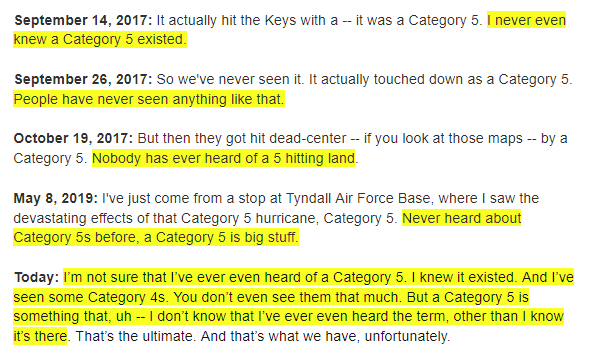

President Trump says he didn’t know Category 5 hurricanes existed

On Sunday, President Trump expressed his surprise over Hurricane Dorian’s Category 5 strength, saying:

“I’m not sure I’ve ever even heard of a Category 5. I knew it existed. And I’ve seen some Category 4s. You don’t even see them that much. But a Category 5 is something that, uh, I don’t know that I’ve never even heard the term, other than I know it’s there. That’s the ultimate. And that’s what we have, unfortunately.”

But the President knew full well that Category 5 hurricanes exist, based on his past comments. As reported today by the Capital Weather Gang’s Andrew Freedman, Trump has expressed shock at the existence of Category 5 storms at least two other times: during Hurricane Irma in 2017 (“never even knew a Category 5 existed”) and Hurricane Michael in 2018 (never heard about Category 5s before.”) Oddly, though, Trump has repeatedly called Hurricane Maria, which devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, a Category 5—even though it was a Category 4 at landfall. Troublingly, since the president is in charge of ordering disaster relief in the wake of a hurricane, his Category 5 misconceptions could lead to a slowing or mis-allocation of resources.

President Donald Trump on the existence of Category 5 hurricanes, 2017-2019.

22.7K people are talking about this

Trump’s Category 5 blindness is also financially dangerous for a businessman who owns a multi-million-dollar property on a barrier island in a hurricane storm surge zone--the Mar-a-Largo resort in Palm Beach, Florida. NOAA’s National Storm Surge Hazard Maps database predicts that Mar-a-Largo would see inundations of up to 3 – 6’ on the back-bay side during a Category 5 hurricane. The resort was evacuated and boarded up for Dorian, after a 1 pm Sunday evacuation order was given for the barrier island.

Also concerning is the President’s failure to understand the size of Dorian. On Sunday, he tweeted: "In addition to Florida – South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama, will most likely be hit (much) harder than anticipated. Looking like one of the largest hurricanes ever.”

In these comments, President Trump confused the strength of the storm for its size. The intensity of a hurricane’s peak winds is not correlated with the areal size, and Dorian is an average-sized hurricane whose winds will come nowhere close to affecting Alabama. Officials there had to scramble to put out statements refuting the President’s misinformation. Unfortunately, he repeated the claim later at a FEMA press conference. He told journalists: "And Alabama could even be in for at least some very strong winds and something more than that, it could be. This just came up, unfortunately. It's the size of the storm that we're talking about. So, for Alabama, just please be careful also.”

Finally, we should be concerned about the President’s reported willingness to use nuclear weapons on hurricanes. According to an August 25, 2019 report from Axios, citing inside sources, during one hurricane briefing at the White House, Trump said (paraphrasing the president's remarks): "I got it. I got it. Why don't we nuke them? They start forming off the coast of Africa, as they're moving across the Atlantic, we drop a bomb inside the eye of the hurricane and it disrupts it. Why can't we do that? Trump has denied making the statement.

If one were to detonate a nuclear device in the eyewall of a hurricane, the radioactive fallout would very efficiently be carried high into the atmosphere due to the tremendous upper-level outflow that ventilates a hurricane. In a matter of days, radioactive fallout would be carried around the globe by the sub-tropical jet stream, contaminating rainfall over a huge area. The blast would also have little or no impact on the hurricane, since the amount of energy released by a nuclear device is puny compared to what a hurricane generates. It is also illegal under the terms of the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union to explode a nuclear weapon in the atmosphere.

Dr. Jeff Masters co-wrote this post, including the section on President Trump.