by John Abraham, "Climate Consensus - The 97%," The Guardian, July 17, 2014

As I sit here in a northern part of the United States (Minnesota), a rare summer arctic blast barrels down from Canada on what otherwise is one of the warmest days of the year. Global warming? I could use some global warming today, people are saying.

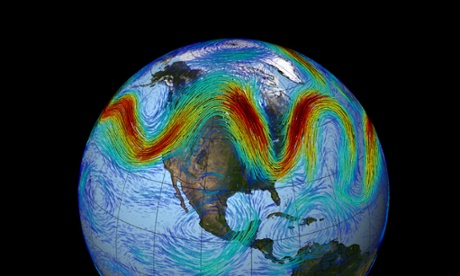

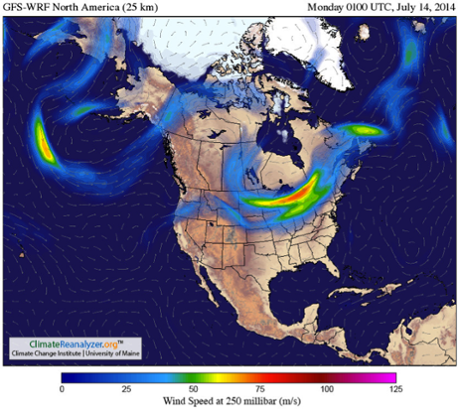

Not only is this a teachable moment, but it coincides with a major new study on climate connections. First, let’s see the current jet stream. It is wildly undulating, first swinging up into northern Canada before curving back and plunging into the central United States.

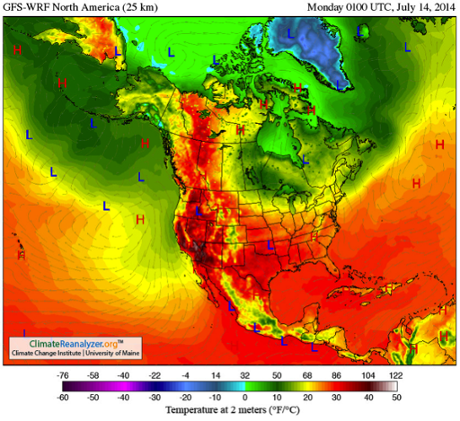

Typically, the jet stream represents a separation between cold arctic air and warmer southern air. If you are north of the jet stream, temperatures are cold whereas south of the jet stream it's more likely to be warm.

With this in mind, and the jet stream shown, you can almost predict the temperature pattern in the next image. The match is incredible and it is clear that my Minnesota cold-blast is more than balanced out by near 90°F temperatures in northern Canada. With all of this, I want to talk about a new study that looks at these fluctuations on a longer term.

Very recently, a paper Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favor particular regional weather extremes was published in the journal Nature Climate Change. The authors, James Screen and Ian Simmonds, investigated the role that changes to upper level winds in the atmosphere have on the occurrence of extreme weather. What they found was very interesting.

People who follow this site and the climate literature no doubt are aware that a hotly debated topic has arisen in recent years. I have written about studies that have linked loss of Arctic ice and warming of the Arctic region to more severe undulations in the jet stream. That research is still in its infancy and consequently, very exciting. While the idea that global warming increases jet stream undulations have been challenged by others, it is clear that some recent observations support the hypothesis.

The latest study is related to this topic but still unique. The authors don’t ask the question “are humans changing the jet stream patterns?” Instead, they ask, “how do undulations in the jet stream affect weather?” To be fully accurate, the study isn’t just about jet streams, it really deals with mid-latitude planetary waves but for this article, I will use the term “jet stream” as a surrogate for simplicity.

The authors went back into our weather records (1979–2012) and found the 40 months with the most extreme weather (most extreme precipitation and most extreme temperatures). They then evaluated how “wavy” the jet stream was during those extreme months. They found that:

months of extreme weather over mid-latitudes are commonly accompanied by significantly amplified quasi-stationary mid-tropospheric planetary waves. Conversely, months of near average weather over mid-latitudes are often accompanied by significantly attenuated waves.

In common parlance, this means that when the jet stream undulates and travels very slowly, we see more extreme weather. Conversely, when the jet stream travels in a straighter path, the weather is less extreme.

This association itself is not new but it brings the connection of large-scale climatic variations and our local weather to the fore of attention. Perhaps more important, however, are the follow-on observations from the authors. In particular, they report:

Depending on geographical region, certain types of extreme weather (for example hot, cold, wet, dry) are more strongly related to wave amplitude changes than others. The findings suggest that amplification of quasi-stationary waves preferentially increases the probabilities of heat waves in western North America and Central Asia, cold outbreaks in eastern North America, droughts in central North America, Europe, and central Asia, and wet spells in western Asia.

Dr. James Screen, a Research Fellow at the University of Exeter and lead author of the study told me,

The impacts of large and slow moving atmospheric waves are different in different places. In some places amplified waves increase the chance of unusually hot conditions, and in others the risk of cold, wet or dry conditions.

To my knowledge, previous investigations have not elucidated the geographical locations of extreme weather nor have they identified the location-dependent weather extremes. It will be interesting to watch present and future weather to determine if these relationships between waves and weather continue.

A note of caution however, we must be mindful that there are other weather factors at play which are superimposed on those discussed in the article. For instance, changes from El Niño to La Niña in the Pacific and long-term variability of sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic are also known to impact our weather extremes. Separating these multiple factors will take skill.

No comments:

Post a Comment