by andyextance, Simple Climate, May 31, 2014

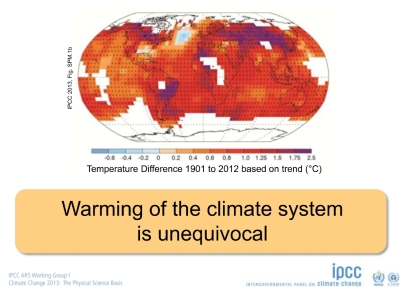

The latest IPCC report has highlighted that it’s dead certain that the world has warmed, and that it’s extremely likely that humans are the main cause. Credit: IPCC

The most recent UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report saw perhaps the most severe conflict between scientists and politicians in the organisation’s existence. As its name suggests, governments take an active part in the IPCC process, whose latest main findings appeared between September 2013 and May 2014. Debate over what information makes the high-profile ‘Summaries for Policymakers’ is usually intense, but this time three graphs were dropped on politicians’ insistence. I show these graphs later in this blog entry.

At the Transformational Climate Science conference in my home town, Exeter, UK, earlier this month, senior IPCC author Ottmar Edenhofer discussed the ‘battle’ with governments on his part of the report. Another scientist who worked on the report highlighted confidentially to me how unusual the omission was.

To me, it’s more surprising that this hasn’t happened more often, especially when you look more closely at the latest report’s findings. There’s concrete certainty that warming is happening, and it’s extremely likely that humans are the dominant cause, it says. Governments have even – in some cases, begrudgingly – already signed up to temperature and CO2 emission targets reflecting this fact.

The inadequacy of those words is becoming ever more starkly obvious. Ottmar stressed that the emissions levels agreed at the United Nations’ Climate Change Conference in Cancún, Mexico, in November 2010, would likely need later emissions cuts the likes of which we’ve never seen before to avoid dangerous climate change. The latest IPCC report shines a floodlight on that inertia, which understandably cranks up the tension between researchers and politicians.

Ottmar was one of two co-chairs who led the ‘working group three’ (WGIII) section of the IPCC report that looks at how to cut greenhouse gas emissions. He stressed that the need to make these cuts comes from a fundamental difference between the risks that come from climate change and the risks of mitigation. We can heal economic damage arising from cutting emissions – reversing sea level rise isn’t so easy.

Our choices are looking increasingly sucky

The three IPCC co-chairs who were at the Exeter conference, from left to right, Chris Field (WGII), Ottmar Edenhofer (WGIII), Thomas Stocker (WGI). The IPCC report is split into three main parts, or working groups, each led by two ‘co-chairs.’ Within each working group there are many chapters, with scientists serving as lead authors or authors on those chapters. Image credit University of Exeter, used via Flickr Creative Commons licence.

The Exeter conference made it clear that the IPCC is also trying hard to highlight ways to meet these targets. Ottmar pointed to two important steps. One was setting a reasonable price on carbon, which would make using fossil fuels more expensive and shift us towards cleaner energy sources. Another was defining the atmosphere as a ‘global commons’ – something that belongs to all of us, which a legal system could be set up to look after. And while the greenhouse gas reduction agreements now in place are insufficient, WGIII lead author Catherine Mitchell stressed that we can learn from the ones that work well.

Yet the IPCC could only offer one scenario that would keep warming below 2 °C from pre-industrial times, the target countries signed up to in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 2009. That scenario advocated an approach that had been barely discussed before: bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, or BECCS. The authors have suggested it because to keep on track for the 2 °C target we’re likely to need to suck CO2 out of the air.

While there are hi-tech ideas for how to do that, the only currently-proven method is an ancient one: growing plants. We can and do burn these plants for energy, but to bring warming under control we need to stop their carbon getting back into the atmosphere – we need to capture and store it. This is the essence of BECCS and while it may seem an elegant solution, Ottmar revealed the debates on its inclusion were intense. One issue was the idea’s sheer obscurity – could the IPCC scientists even be confident it can be done? Another is that growing plants for fuel brings competition for land currently used for food.

When would climate change losses become unbearable for you?

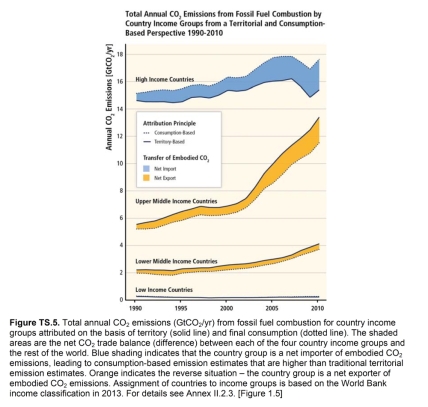

The third of the graphs politicians stopped being included in the IPCC WGIII Summary for Policymakers. It shows that a growing share of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes in low and middle income countries has been released in the production of goods and services exported, notably from upper‐middle income countries to high income countries. Image credit: IPCC

Another new idea in the latest IPCC report has been discussion of ethical issues, like how BECCS might threaten people’s ability to meet their basic needs. WGIII author Simon Caney highlighted that our moral outlooks can determine how widely technologies like fracking, nuclear power and geoengineering are used. Moral arguments also enter climate negotiations, for example limiting the case for including past emissions because the older generation didn’t know what burning fossil fuels was doing. Simon stressed that future analyses must include ethical aspects better, bringing in energy justice by looking at whose interest emissions are serving.

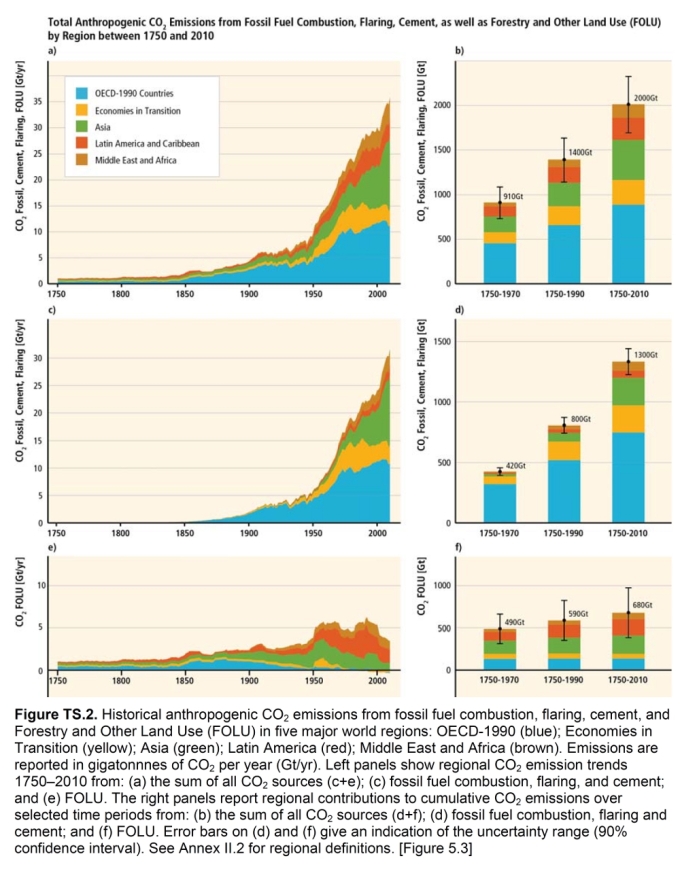

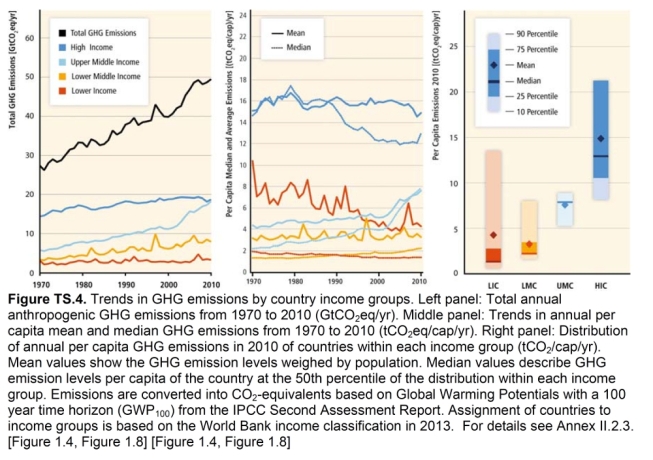

But it was such implications for negotiations that politicans objected to in the WGIII SPM. The first excluded graph showed that since the 1970s growth in total greenhouse gas emissions came mostly from developing countries. The second showed emissions per person have grown rapidly in middle-income countries like China and India, but have fallen in both the richest and the poorest countries. However, emissions remain much higher per person in the developed world. The final graph showed that the goods developed countries are importing are producing significant CO2 elsewhere, unbalancing the worldwide effort to cut emissions.

Despite the conflict these graphs and their implications caused, values-guided science still looks set to play a bigger role for the IPCC. For example, one suggestion at the Exeter conference was value-based scenarios for what the future might look like, and how greenhouse gas emissions might be shared. Our values are also important in setting the real limit to climate change – the point at which we are no longer willing to adapt. That was a question highlighted by Frans Berkhout, a lead author on one of theworking group two chapters: If we can adapt to everything, why fight global warming? Because some of our values are non-negotiable – I’d be unwilling to give up my home, for example – I’d hate to be forced to adapt by moving. And in fact, Frans noted, there will be damages and losses caused by the changes we can’t stop or adapt to. At what point are these losses intolerable?

WGII’s focus is both adaptation and the impacts of climate change. Chris Field, one of two co-chairs who led this part of the report, underlined that the impacts are felt on all continents, from the coasts to the mountains. But for me the one question about impacts that hit home harder than any other was about the big picture on nutrition and food availability. What happens if we get two or three years that are really bad for farming worldwide?

How can we get real solutions?

IPCC WGII co-chair Chris Field tells the Exeter conference about climate change impacts and adaptation.

Chris also made some refreshingly honest confessions. Even hundreds of scientists, who have together produced a report millions of words long, aren’t enough to make governments take up its suggestions, he admitted. Chris also doesn’t know how to move from producing a ‘massively rich’ document to a dialogue that leads to real solutions. And he also concedes that the report’s very richness may also sometimes be counterproductive. There are so many caveats that people can say fighting climate change is too dear, or dirt cheap, and both be right. And finally, he also admitted to being mystified about how the IPCC process can even work. Why don’t countries that dislike the IPCC oppose everything it tries to put in the Summaries for Policymakers?

As vast as the IPCC reports so far have been, Chris’ comments make an important truth clear. Even our best evidence alone is not enough to resolve a problem caused by the same resources that put our society in a place to reveal that evidence. Fossil fuels have given many of us comfortable lives, and if it weren’t for climate change their full exploitation would be a no-brainer. Giving them up, or even making them more expensive through carbon pricing, is a big step. It’s hardly surprising we’re slow to do it.

But the IPCC report does make a compelling case for why we must. So, where scientists have started others must continue. I use my vote and voice to try to persuade politicians to take the situation seriously – I hope you do too. Yet many people still don’t do this. It’s easy to think that they’re wrong, and perhaps accuse them of not caring about their future or that of their children. However, in a democratic world all such viewpoints should be considered, and so it’s up to us to work together to find a way forward.

In the climate change debate, where heightened passions can quickly descend into name-calling, for me the key is trust. We must each decide if and exactly why scientists deserve our trust. Having seen the efforts of the IPCC scientists in person has renewed my trust in their work, and I’d recommend that you trust it too. That then leads onto the other levels of trust we need – trust between us as individuals and as nations. If we can get a workable level of trust, then maybe the lessons and suggestions of the IPCC can be fully taken on board.

The first of the graphs that politicians prevented from inclusion in the IPCC WGIII Summary for Policymakers. It shows developed countries are now responsible for less than half of total human caused (anthropogenic) historical greenhouse gas emissions. Consequently negotiating a climate deal on the basis of historical responsibility for emissions looks like an idea that might backfire on its proponents in the developing world. Image credit: IPCC

The second of the graphs politicians stopped from being used in the IPCC WGIII Summary for Policymakers. It shows that developed countries still emit the most, but that upper-middle income countries like India and China have gained rapidly. Image credit: IPCC

- Videos and slides from the Exeter conference are available here

- These other blog entries give different viewpoints of the event:

Journal reference

Kintisch, E. (2014). In New Report, IPCC Gets More Specific About Warming Risks Science, 344 (6179), 21-21 DOI: 10.1126/science.344.6179.21

http://simpleclimate.wordpress.com/2014/05/31/ipcc-millions-of-words-on-climate-change-are-not-enough/

Kintisch, E. (2014). In New Report, IPCC Gets More Specific About Warming Risks Science, 344 (6179), 21-21 DOI: 10.1126/science.344.6179.21

http://simpleclimate.wordpress.com/2014/05/31/ipcc-millions-of-words-on-climate-change-are-not-enough/

No comments:

Post a Comment