Vast East Siberian Arctic Shelf methane stores destabilizing and venting

NSF issues world a wake-up call: "Release of even a fraction of the methane stored in the shelf could trigger abrupt climate warming.”

by Joseph Romm, Climate Progress, March 4, 2010

Methane release from the not-so-perma-frost is the most dangerous amplifying feedback in the entire carbon cycle. Research published in Friday’s journal Science finds a key “lid” on “the large sub-sea permafrost carbon reservoir” near Eastern Siberia “is clearly perforated, and sedimentary CH4 [methane] is escaping to the atmosphere.”

Scientists learned last year that the permafrost permamelt contains a staggering “1.5 trillion tons of frozen carbon, about twice as much carbon as contained in the atmosphere,” much of which would be released as methane. Methane is is 25 times as potent a heat-trapping gas as CO2 over a 100-year time horizon, but 72 times as potent over 20 years!

The carbon is locked in a freezer in the part of the planet warming up the fastest (see “Tundra 4: Permafrost loss linked to Arctic sea ice loss“). Half the land-based permafrost would vanish by mid-century on our current emissions path (see “Tundra, Part 2: The point of no return” and below). No climate model currently incorporates the amplifying feedback from methane released by a defrosting tundra.

The new Science study, led by University of Alaska’s International Arctic Research Centre and the Russian Academy of Sciences, is “Extensive Methane Venting to the Atmosphere from Sediments of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf” (subs. req’d). The must-read National Science Foundation press release (click here), warns “Release of even a fraction of the methane stored in the shelf could trigger abrupt climate warming.” The NSF is normally a very staid organization. If they are worried, everybody should be.

It is increasingly clear that if the world strays significantly above 450 ppm atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide for any length of time, we will find it unimaginably difficult to stop short of 800-1000 ppm.

Note: As part of the Climate Science Project, I’m making this post as definitive as I can by including other recent scientific findings on the tundra. Please add other relevant links in the comments.

The lead author, Natalia Shakhova, explains the new findings in this video:

NSF explains:

“The amount of methane currently coming out of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is comparable to the amount coming out of the entire world’s oceans,” said Shakhova, a researcher at UAF’s International Arctic Research Center. “Subsea permafrost is losing its ability to be an impermeable cap.”

Methane is a greenhouse gas more than 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide. It is released from previously frozen soils in two ways. When the organic material (which contains carbon) stored in permafrost thaws, it begins to decompose and, under anaerobic conditions, gradually releases methane. Methane can also be stored in the seabed as methane gas or methane hydrates and then released as subsea permafrost thaws. These releases can be larger and more abrupt than those that result from decomposition.

The East Siberian Arctic Shelf is a methane-rich area that encompasses more than 2 million square kilometers of seafloor in the Arctic Ocean. It is more than three times as large as the nearby Siberian wetlands, which have been considered the primary Northern Hemisphere source of atmospheric methane. Shakhova’s research results show that the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is already a significant methane source, releasing 7 teragrams of methane yearly, which is as much as is emitted from the rest of the ocean. A teragram is equal to about 1.1 million tons.

“Our concern is that the subsea permafrost has been showing signs of destabilization already,” she said. “If it further destabilizes, the methane emissions may not be teragrams, it would be significantly larger.”

Shakhova notes that the Earth’s geological record indicates that atmospheric methane concentrations have varied between about 0.3-0.4 ppm during cold periods to 0.6-0.7 ppm during warm periods. Current average methane concentrations in the Arctic average about 1.85 ppm, the highest in 400,000 years, she said. Concentrations above the East Siberian Arctic Shelf are even higher.

The East Siberian Arctic Shelf is a relative frontier in methane studies. The shelf is shallow, 50 meters (164 feet) or less in depth, which means it has been alternately submerged or terrestrial, depending on sea levels throughout Earth’s history. During the Earth’s coldest periods, it is a frozen arctic coastal plain, and does not release methane. As the Earth warms and sea level rises, it is inundated with seawater, which is 12-15 degrees warmer than the average air temperature.

“It was thought that seawater kept the East Siberian Arctic Shelf permafrost frozen,” Shakhova said. “Nobody considered this huge area.”

Last August, I discussed findings by German and British scientists “that more than 250 plumes of bubbles of methane gas are rising from the seabed of the West Spitsbergen continental margin in the Arctic, in a depth range of 150 to 400 metres” (see “So many amplifying methane feedbacks, so little time to stop them all” and figure on right).

Last August, I discussed findings by German and British scientists “that more than 250 plumes of bubbles of methane gas are rising from the seabed of the West Spitsbergen continental margin in the Arctic, in a depth range of 150 to 400 metres” (see “So many amplifying methane feedbacks, so little time to stop them all” and figure on right).A lead researcher of that work said, “Our survey was designed to work out how much methane might be released by future ocean warming; we did not expect to discover such strong evidence that this process has already started.”

But the situation in the ESAS is far, far more dicey, as NSF explains:

The East Siberian Arctic Shelf, in addition to holding large stores of frozen methane, is more of a concern because it is so shallow. In deep water, methane gas oxidizes into carbon dioxide before it reaches the surface. In the shallows of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, methane simply doesn’t have enough time to oxidize, which means more of it escapes into the atmosphere. That, combined with the sheer amount of methane in the region, could add a previously uncalculated variable to climate models.

“The release to the atmosphere of only one percent of the methane assumed to be stored in shallow hydrate deposits might alter the current atmospheric burden of methane up to 3 to 4 times,” Shakhova said. “The climatic consequences of this are hard to predict.”And we also know that a key trigger for accelerated warming in the Arctic region is the loss of sea ice.

A 2008 study by leading tundra experts found “Accelerated Arctic land warming and permafrost degradation during rapid sea ice loss.” The lead author is David Lawrence of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), whom I interviewed for my book and interviewed again via e-mail in 2008. The study’s ominous conclusion:

We find that simulated western Arctic land warming trends during rapid sea ice loss are 3.5 times greater than secular 21st century climate-change trends. The accelerated warming signal penetrates up to 1,500 km inland…In other words, a continuation of the recent trend in sea ice loss may triple Arctic warming, causing large emissions in carbon dioxide and methane from the tundra this century.

Oh, and the Arctic warming could lead to another feedback according to a 2008 Science article:

“Continuation of current trends in shrub and tree expansion could further amplify this atmospheric heating 2-7 times.”

The point is that if you convert a white landscape to a boreal forest, the surface suddenly starts collecting a lot more solar energy (see “Tundra 3: Forests and fires foster feedbacks“).

That trend is occurring now, as seen in these two photos from a recent ScienceNews article, “Boreal forests shift north.”

That trend is occurring now, as seen in these two photos from a recent ScienceNews article, “Boreal forests shift north.”“Upper photo taken in 1962 shows tundra-dominated mountain slope in Siberian Urals. A 2004 photo of the same site, below, shows conifers were setting up dense stand of forest.”

Another major study warns that the warming-driven northward march of vegetation poses yet another threat to the tundra: “Greater fire activity will likely accompany temperature-related increases in shrub-dominated tundra predicted for the 21st century and beyond.” The concern is not so much the direct emissions from burning tundra, but the albedo change.

And all that warming would cause massive melting of the tundra and faster emissions release. That must be avoided at all cost, since the tundra feedback, coupled with the climate-carbon-cycle feedbacks that the IPCC models, could easily take us to the unmitigated catastrophe of 1000 ppm.

And all that warming would cause massive melting of the tundra and faster emissions release. That must be avoided at all cost, since the tundra feedback, coupled with the climate-carbon-cycle feedbacks that the IPCC models, could easily take us to the unmitigated catastrophe of 1000 ppm.The good news is that a 2009 NOAA-led study found “Near-zero CH4 growth in the Arctic during 2008 suggests we have not yet activated strong climate feedbacks from permafrost and CH4 hydrates” (see “Is it just too damn late?“)

The bad news is we clearly are on very thin ice. Literally.

Lawrence revised and updated his 2005 analysis of tundra loss under different emissions scenarios (after some scientists criticized the original work) in this 2008 study, “Sensitivity of a model projection of near-surface permafrost degradation to soil column depth and representation of soil organic matter” (subs. req’d). The updated analysis still found: “the warming is enough to drive near-surface permafrost extent sharply down by 2100.”

I had asked Lawrence if it was still reasonable to keep using this figure in my presentation, since it is so much easier to understand than the figures in his new paper.

He said, “Using the old figure is still fine as long as one mentions the caveats that permafrost is probably degrading a bit too rapidly in the original.

So I will certainly use that caveat, though, of course, I will also caveat the caveat by saying the slightly slower rate of permafrost degradation does not include Lawrence’s new analysis on the accelerated warming of the permafrost due to sea ice loss (or, for that matter, the accelerated warming of the permafrost due to faster shrub encroachment).

Note that the “B1″ scenario stabilizes CO2 concentrations in the air at 550 ppm — and the near-surface permafrost permafrost (down to 11 feet) plummets from over 4 million square miles today to 1.5 million. If concentrations hit 850 ppm in 2100 (A2), permafrost would shrink to just 800,000 square miles.

And while these projections were done with one of the world’s most sophisticated climate system models, the calculations do not include the feedback effect of the released carbon from the permafrost. That is to say, the CO2 concentrations in the model rise only as a result of direct emissions from humans, with no extra emissions counted from soils or tundra. Thus, they are conservative numbers – or overestimates – of how much CO2 concentrations have to rise to trigger irreversible melting.

In short, the would-be point of atmospheric stabilization, 550 ppm isn’t stable at all — it is past the point of no return. We must stay well below 450 ppm to save the tundra and hence the climate. The new research underscores that conclusion, especially since the planet will keep warming (slowly) for decades even once we slash emissions to near zero.

And that means we must begin a staggering amount of clean energy deployment as soon as possible (see “How the world can (and will) stabilize at 350 to 450 ppm: The full global warming solution“).

Wake up media and politicians who are being duped by the anti-science disinformers into thinking there is any serious doubt about the catastrophe we face on our current path of unrestricted emissions!

UPDATE: WWF’s Nick Sundt points out:

A report released by the U.S. Global Change Research Program,Abrupt Climate Change, said in December 2008 (during the Bush Administration) that warming in the Arctic could cause sea levels to rise substantially beyond scientists’ previous predictions and could result in massive releases of methane. The report said that the “rapid release to the atmosphere of methane trapped in permafrost and on continental margins” was among “four types of abrupt change in the paleoclimatic record that stand out as being so rapid and large in their impact that if they were to recur, they would pose clear risks to society in terms of our ability to adapt.”The NSF has a good fact sheet, “Questions and Answers on Potentially Large Methane Releases From Arctic, and Climate Change.”

UPDATE: Since we don’t have a time series of CH4 emissions from the shelf, we can’t know for certain that these emissions levels are new or growing. But as the study makes clear, they are unexpectedly high and the lid is perforated:

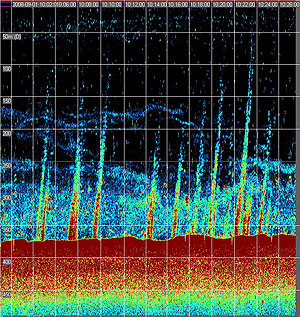

They found that more than 80% of the deep water and more than 50% of surface water had methane levels more than 8 times that of normal seawater. In some areas, the saturation levels reached more than 250 times that of background levels in the summer and 1,400 times higher in the winter. They found corresponding results in the air directly above the ocean surface.

Methane levels were elevated overall and the seascape was dotted with more than 100 hotspots. This, combined with winter expedition results that found methane gas trapped under and in the sea ice, showed the team that the methane was not only being dissolved in the water, it was bubbling out into the atmosphere.

These findings were further confirmed when Shakhova and her colleagues sampled methane levels at higher elevations. Methane levels throughout the Arctic are usually 8-10% higher than the global baseline. When they flew over the shelf, they found methane at levels another 5-10% higher than the already elevated Arctic levels.So yes, there is the possibility this is a grand coincidence — but that would not eliminate the fact that the lid on these vast methane stores is perforated and emissions are poised to rise sharply as temperature rises and none of this is in any of the global climate models. How much is the business as usual warming now projected for the region? Try M.I.T. doubles its 2095 warming projection to 10 °F — with 866 ppm and Arctic warming of 20 °F.

The nations of the world should immediately begin emergency methane monitoring across the entire permafrost region — and, of course, aggressive GHG mitigation. The risk of abrupt climate change is simply too grave to not treat as the most serious preventable problem now facing the human race as a whole.

[the comments at the link below are also well worth reading]

Link: http://climateprogress.org/2010/03/04/science-nsf-tundra-permafrost-methane-east-siberian-arctic-shelf-venting/

No comments:

Post a Comment